The Lure of Nature

The Lure of Nature

How Nathaniel Gillespie ’92 turned his passion into a career.

BY MELISSA ULSAKER MAAS ‘76

On his senior page in the 1992 SSSAS “Traditions” yearbook, Nathaniel Gillespie mentions treehugging, fly fishing in Montana, Cocoa Beach, and a shark. Nat picked two photos to accompany his senior portrait, one of his family standing by water on an outdoor adventure complete with binoculars and one of him fishing. The things that were most important to him then, are still close to his heart now—family, fish, and the environment.

From Nat’s senior page in the 1992 yearbook.

Today Nat is a passionate and visionary conservation professional working for the U.S. Forest Service as their assistant fish program leader. With a focus on freshwater fish, he provides leadership in coordination with the National Fisheries Program leader in developing and implementing fisheries related strategies, providing guidance, coordination, and direction among a large, geographically dispersed staff of nine regional office fisheries programs. He has experience leading team-based, collaborative approaches to developing policy, communicating ecological and socioeconomic values, and solving complex aquatic and social challenges in aquatic, recreation, and infrastructure arenas. He currently works with eight regional offices that manage almost 200 million acres, including 155 spectacular national forest and grasslands in 42 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. Nat loves his job and wants to inspire people to respect, celebrate, and conserve our aquatic environments to benefit the natural world and the communities that depend on them.

Where It All Began

Nat’s description of his youth is pretty idyllic. “As a kid I was really interested in fish and the outdoors, and that interest was cultivated over a whole lifetime by my parents and grandparents. My grandfather was a fly fishing expert, so I fished with him in the summer in the New York Catskills.” Sometimes his family took him farther afield, to some of our county’s most beautiful locations. Nat’s reference to Montana on his senior page is about an outstanding fishing trip he took with his dad and grandfather when he was 14. “We went fishing for a week outside of Yellowstone National Park, which was mind-blowing,” he recalls. “Not only was the scenery amazing, but fishing together is always a great bonding experience.” When he was 16 and 17, he returned to work at the same fly fishing shop for two summers where he sold fishing gear, explored Yellowstone National Park on his bicycle and soaked in everything about the recreational fishing industry from the professional guides.

Nat’s interest in the environment was enriched and encouraged at St. Stephen’s. As he talks about his teachers, he grows more and more animated. “When I think about St. Stephen’s, I immediately think about some of the teachers that were so influential and supportive,” he says. “My friends and I still talk about our Middle School teacher Mr. Atwood today, because he was so passionate. He was like a leprechaun figure with his giant red beard, and he was so dynamic with such a curious, detailed mind.” Fred Atwood also supervised the unusual Upper School Bird Banding Club. Nat founded and co-led the Recycling Club with classmate Greg Gallagin, which kept him busy, but he participated in the Bird Banding Club whenever he could. “It really influenced me,” Nat says. “It was incredible to me that you could set up these very fine mesh nets in the woods or in a field to catch the birds, measure them, put little metal bands on their legs, and track their movements across the east or even the country. I ended up learning all about local species, like the pileated woodpecker and dark-eyed junco.”

That was just one of many real wildlife biology experiences Nat enjoyed at school. In Upper School Nat was captivated by science teachers Anna Vascott and Douglas Bryant. “I had several incredible outdoor experiential classes,” Nat says. “In Field Natural History, for example, we would go outside for two to three hours visiting local public lands and parks to chronicle the wildlife and learn about the different environments. We frequented the wetlands at Huntley Meadows and the stream systems at Prince William Forest, which were pretty intact compared to the local streams that were so degraded by the urbanization and stormwater.”

What’s the Difference?

The U.S. Forest Service vs. National Park Service

The U.S. Forest Service, which manages our country’s National Forests and Grasslands, is under the Department of Agriculture, while the National Park Service is within the Department of the Interior. The greatest difference between the two is the multiple-use mandate for National Forests. While National Parks are managed with preservation as a top priority, barely altering the existing state, the goal of the National Forests is to achieve quality land management under the sustainable multiple-use management concept to meet the diverse needs of people. The U.S. Forest Service tagline is the Land of Many Uses. The U.S. Forest Service provides protection for water, timber, and fish and wildlife, but also allows, with fairly high regulation, mining and cattle and livestock grazing. Visitors can go camping, fishing, hunting, and horseback riding.

Find a forest or grassland and explore the U.S. Forest website at fs.usda.gov.

In Roger Barbee’s English class, Nat was surprised to discover a number of books on fly fishing on his classroom shelves. “There are more books on fly fishing per capita than any other subject in the world,” Nat explains. “People who fly fish love to talk about it and what they’ve learned, and how it relates to life and God and everything. Since Mr. Barbee exposed me to this fly fishing conservation literature I’ve read hundreds of these books.” Roger Barbee remembers Nat well, “I have such a fond memory of Nat’s interest in fly fishing. He read every book I gave him, always shared his experiences with me, and even presented me with some fly lures because he had learned to tie them himself.”

Nat says he is grateful to all his English teachers because writing has been very important to his career. “They forced us to learn how to write short stories, which was very hard, but it’s helped me in my professional career,” Nat says. “I’ve written a lot of popular level conservation articles for a broad audience and I take a lot of pride in that.” Nat has also written a number of more scientific manuscripts that were peer-reviewed. He credits two years with Dr. Judy Brent as his foundation for learning how to think critically and analytically, and to question the author’s voice and context of historical time.

“I’ve witnessed so many changes in the places I fished as a boy, places I take my children to fish now. This has greatly contributed to my understanding of the environment, how nature works, and how we influence it.”

“That kind of thinking has also played into my career as a conservationist, because having an analytical mind and exercising the powers of observation are qualities of a naturalist, and qualities of such legendary conservationists like E.O. Wilson and Jane Goodall,” Nat continues. He feels that one of the most important things he’s learned over time is the value of intense observation, paying attention to his surroundings, and chronicling the changes—which he has spent years doing while fishing locally. “I’ve witnessed so many changes in the places I fished as a boy, places I take my children to fish in now,” Nat says. “This has greatly contributed to my understanding of the environment, how nature works, and how we influence it. So, a lot of those childhood adventures fishing and observing, and wondering why things are the way they are, have really stuck with me.”

For instance, Nat vividly remembers the invasion of the hydrilla on the Potomac River when he was a boy. “This giant mass of dark green vegetation covered the entire river in the 1980s,” Nat says. “It’s an invasive species that helped process all the phosphorus and nitrogen in the water. That improved the water quality to the point that native plants which weren’t thriving could come back. Between the hydrilla, the upgrades at Blue Plains treatment plant, the enforcement of the Clean Water Act, and other best management practices happening across the Bay, the Potomac really improved.”

Nat fishing in Rock Creek Park near his home in Washington, D.C. He makes his own fishing lures and carries this collection with him on his fishing adventures.

Exploring Local Waters

Nat and a group of friends enjoyed fishing together and found the local area had much to offer. He and classmate Hossein Nosirvani, who lived on Lake Barcroft, would meet at dawn, grab the amazing Iranian lunch Hossein’s mom made for them, and fish all morning. There were other happy times spent with classmates Jimmy Blackburn, Andrew McCain, and Luke Taylor fishing at Dyke Marsh. He and Luke became so intrigued they decided to do a water study for their senior project.

“The opportunity to do a senior project was such an amazing part of the education,” Nat says. “Luke and I compared a relatively small stream in an urban environment—Four Mile Run—with a relatively small stream in a much more agricultural and forested watershed environment—the Thornton River in Sperryville at the base of Shenandoah National Park.”

They took water quality samples and looked at the aquatic insects, employed fish traps and went fishing to catch and catalog fish, and used what they had learned from their classes to determine what kind of environmental conditions they could likely point to based on their data. Nat says the difference was staggering. “Four Mile Run was clearly impaired and polluted evidenced by the types of fish that were in there and the lack of different types of insects and fish species,” Nat explains. “The stream near Sperryville was in much better shape, although not perfect. There was some impairment from the town, and probably some from agriculture as well, but that’s the kind of science experiment that’s real.” Nat has returned to the same streams 20 and 30 years later to find that the condition of both have improved based on the data from his observations over time. In fact, when he worked with Trout Unlimited, he led the removal of an old mill dam on the Thornton River on a farmer’s property to help migrating fish.

Nat, his wife Elaine, 9-year-old daughter Eva, and 12-year-old son Darren live in Washington, D.C., not far from Rock Creek Park. They love to be outside as often as possible, hiking, exploring, and of course, fishing.

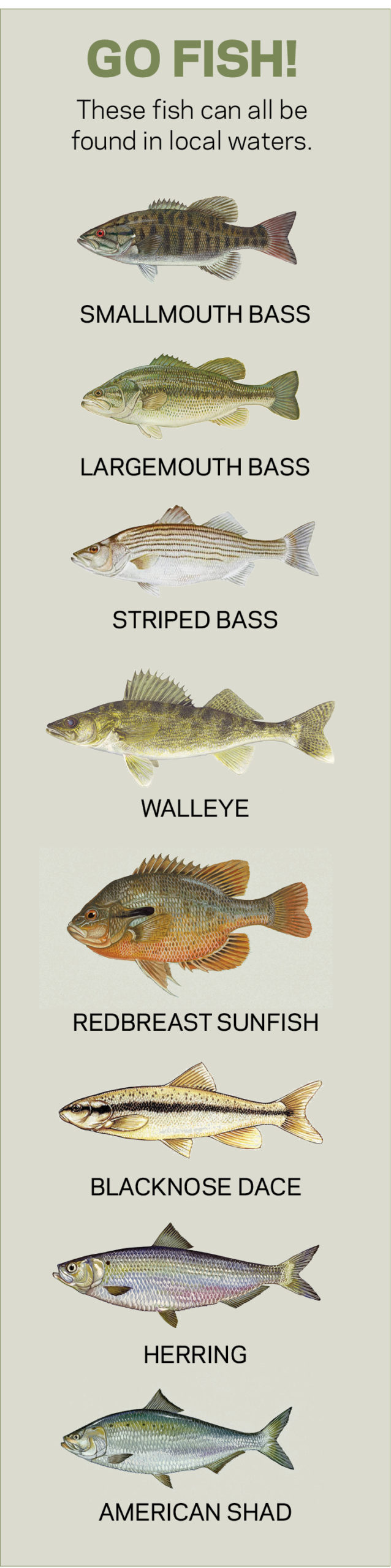

“Although it’s a polluted urban stream, it is still full of life!” Nat said. “I have fished it for almost 20 years and caught many species of sunfish, smallmouth and largemouth bass, fallfish and catfish, and even striped bass and walleye. I also see many herons and eagles visiting the creek alongside the roar of commuting traffic. The creek is a gem in this urban area.”

One surprise to discover in Rock Creek is a fish ladder. As part of the mitigation for the impacts to the Potomac River when the Wilson Bridge was expanded a decade ago, The National Park Service built the ladder at Pierce Mill dam and replaced a number of other barriers to fish migration, like old concrete fords and sewer lines. “As a result, Atlantic Ocean fish like river herring and sea lamprey, and fish from the Chesapeake Bay, like gizzard shad, can swim up the little water staircase past the dam and beyond into many more miles of Rock Creek,” Nat explains. “There they can spawn and make lots more baby fish, who then travel downstream into the Potomac River and back to the Bay and ocean.” Over the years Nat has watched the stream recover. Each spring you can find him at the ladder or walking the creek watching schools of hundreds of herring fight their way upstream.

There are also many non-native fish, mussel, and plant species making their home in the Potomac River and Bay area, of which Nat says one of the most infamous is the snakehead. “I have seen them at Little Falls above Chain Bridge and in Rock Creek above the zoo. They are big and scary looking and can reach 15 pounds or so, but research suggests they have not really upset the food web in the river.”

However, according to Nat, the much larger character in the Potomac is the invasive blue catfish. Between 1974 and 1985, blue catfish were stocked in the James, Rappahannock and York Rivers in Virginia. Since then, their population in the Potomac River has exploded. Apparently, they can grow to more than 100 pounds, eat anything they can fit in their mouths, and are blamed for the decline of several species of fish like redbreast sunfish and shad.

Two years ago, Nat and Darren had an unforgettable encounter. “We were fishing for catfish from a boat at Fletcher’s Cove and Darren hooked a long green hand fishing line on his hook,” Nat says. “I was barely able to haul in the line as we were drifting downstream in the current and quickly realized there was a large fish attached. Suddenly a mouth as big as a five-gallon bucket greeted me at the surface—a blue catfish about three feet long and around 40-50 pounds that looked like it had swallowed a watermelon!” The fish was too heavy for Nat to lift into the boat and way too big for their net, so he reached into the giant mouth with his pliers and cut the hook to let the beast go.

Fishing family fun, Nat and his wife, Elaine, son Darren, and daughter Eva.

Fishing family fun, Nat and his wife, Elaine, son Darren, and daughter Eva.

“The Forest Service manages some of the most amazing fish habitats across the country. I’m involved with stream and floodplain restoration, as well as fixing up old mines from the gold rush from 100 years ago.”

Looking back at his childhood, Nat hopes to encourage the same love and respect for nature that his parents gave to him. “I really give my mom and dad a ton of credit because they gave me the independence and the opportunity to explore,” Nat said with a grin. The first time Nat ever saw a blacknose dace was at Taylor Run. He had never seen any in the stream behind his house, which was too polluted and too shallow, but he would catch the little fish at Taylor Run, take them home, and observe them in his fish tank for years. Discovering that incredible world underneath the surface of the water inspired one of the

most amazing partnerships Nat has helped develop and manage with the forest service, an underwater film NGO, Freshwaters Illustrated. “We’ve done many films with them about the life on waters in the national forests, which are oftentimes very, very well protected, and all the wondrous things that happen with the unseen biology underwater,” Nat says. Because most people are not exploring under the freshwater surface, they developed a youth snorkeling program using a wonderful program from the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee. Nat helped expand the program and U.S. Forest Service biologists now work with schools, including elementary grade students, to outfit them with wet suits, snorkels, and other necessary gear for underwater exploration.

Nat’s advice to students is to focus on something they feel passionate about. “When you love what you do, it’s not work, it’s a joy and a gift,” Nat said. “That’s the bottom line with my whole career. I feel so fortunate to be working in a field that I really care about with other like-minded passionate, dedicated people. I get to be outside once in a while too, which is something that I really value, and I feel like I’m contributing in a small way to making things better for our public lands.” And, of course, he says everyone should spend a little time fishing.

Recreational Fishing is Fun and Beneficial

Fishing is a very healthy pastime that can be enjoyed at any age! From lowering cortisol levels to increasing physical strength, fishing comes with a host of benefits. There’s a reason that fishing is one of the most popular recreational activities in the world.

Gets You Outside

Being in the sun boosts your vitamin D, improves healing times, concentration, and mood.

Fishing is Relaxing

Time spent in nature can reduce blood pressure, improve your focus, and help you develop more patience, and you only need to spend about 30 minutes each week to start seeing the effects.

Improves Cardiovascular Health

Fishing is a great low-impact exercise that can help keep you fit or shed a few pounds. People who are actively fishing can burn an additional 200 calories per-hour walking to find the best spots, recasting the line, and (fingers crossed) reeling in a fish.

A Breath of Fresh Air

Nature helps expose your lungs to more fresh air and clears your head. Being around water is shown to positively impact oxygen levels, as moving water can improve air quality.

Improves your self esteem

Fishing requires you to master a variety of different skills and set goals. Attaining those goals is a sure-fire way to improve self-esteem.

Teaches Self-Reliance

The more involved you get in the sport the more you’ll learn: from driving a boat to hunting down tackle to cleaning, cooking and eating a fish.

Improves Balance and Dexterity

As anyone who has ever reeled a catfish into a canoe can tell you, fishing requires some acrobatic maneuvers. Balance requires core strength and benefits flexibility, both of which help offset back pain.

It’s a day well spent!

No matter what age you are, fishing is a great way to spend a day bonding and connecting with friends and family, enjoying Nature and being outside.