The Accidental Activist Who Helped Change History

The Accidental Activist Who Helped Change History

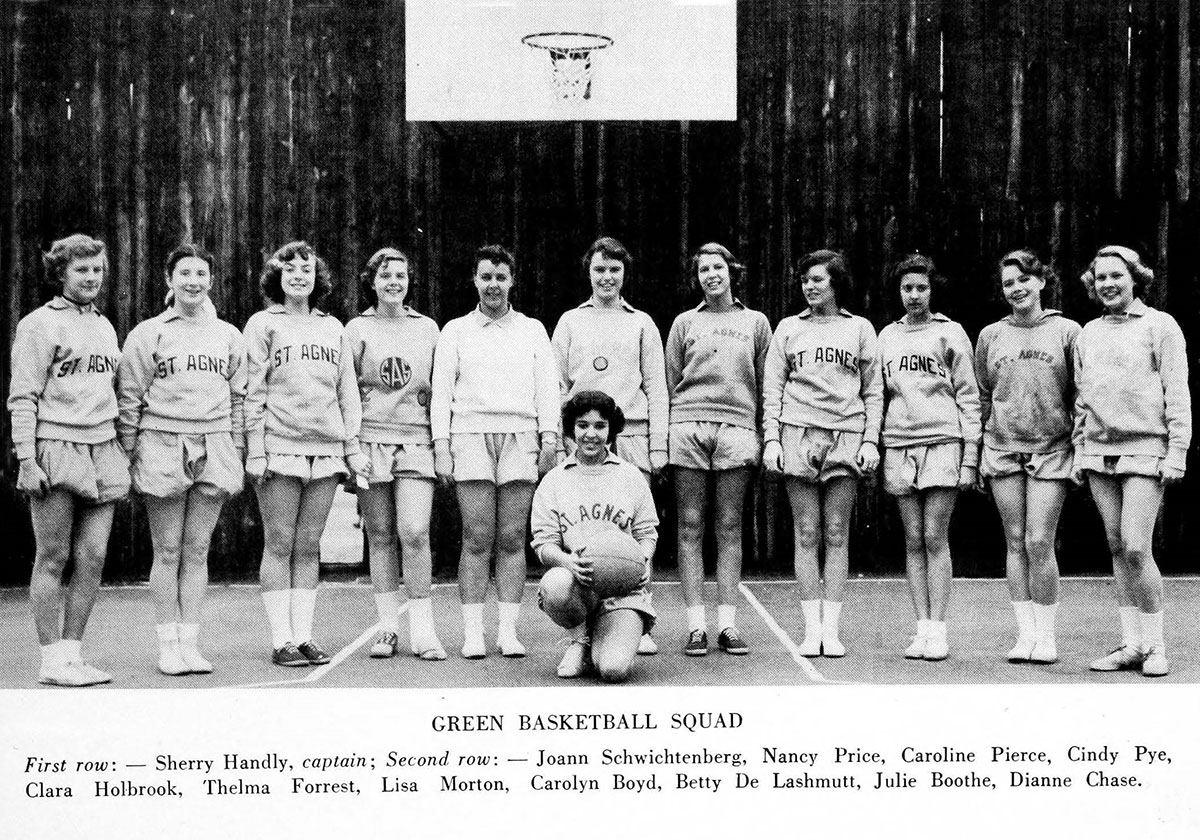

Sharron “Sherry” Handly Martin ’52

BY TAYLOR BALDWIN KILAND ’85

Above portrait by Jamie Howren ’85

It was 2:30 a.m., on July 9, 1967, when 8-year-old Michelle Martin heard a loud knock at the front door of her Coronado, Calif., home. In 1967, this small town was full of Navy families, and the Martins were no exception.

The island was full of aviators who flew jets and helicopters on and off the island at Naval Air Station North Island, and Navy SEALs who trained in the ocean and on the beach at the Naval Amphibious Base. The sounds of jets flying low overhead and the sights of Navy SEALs running in formation on the beach were common ones. Coronado felt like a small southern town—but in southern California. The village had one stoplight, one high school, one library, one all-night diner, and lots of gossip. It also boasted a historic hotel, the Hotel Del Coronado, with its iconic red turrets. The Del was a popular playground for the rich and famous who traveled from all over the world to see the Victorian resort perched on the edge of the Pacific Ocean and to experience the island’s near-perfect, year-round climate. It was seventy degrees and sunny nearly every day.

Nicknamed the Emerald Isle, Coronado in the 1960s was a paradise for military families, a cocoon in which to wait for the many dads who deployed to war zones for months on end. No one locked their doors and kids biked everywhere. They spent weekends surfing, playing volleyball, and lounging late into the night at beach bonfires. On this cool summer night, the head of the Martin household, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Ed Martin, was gone again for a long deployment to the Pacific. His family knew he was fighting in Vietnam, like many of the dads who lived here.

Sleeping adjacent to the front hall, Michelle was jolted awake by the sharp rap at the door. Rubbing her eyes, she jumped out of bed. “It totally scared me,” she remembers. Clad in her nightgown, she slowly opened the front door. There, silhouetted by the porch light, was a man standing erect in his Navy uniform, his face ghoulishly illuminated by a flashlight under his chin. He asked to speak to her mother, Sherry Martin.

Sherry and Ed’s wedding in 1958.

Michelle ran down the hall to wake Sherry, a graduate of the St. Agnes Class of 1952. She, too, was startled by the commotion on the front porch, but Sherry’s maternal instincts kicked in. “Go back to bed, honey. Everything is fine.”

Sherry knew everything was not fine. Military families like the Martins did not receive visits in the middle of the night from U.S. government officials unless something had gone terribly wrong.

Composing herself, Sherry approached the man at her front door, dreading what she was about to hear. Solemnly, he delivered the news: Ed’s A-4 Skyhawk attack plane had been shot down while on an air strike over North Vietnam. He had managed to safely eject from his plane and parachute to the ground, where Ed was immediately surrounded by villagers. It was assumed he was captured, but they honestly did not know. Ed was missing in action.

Sherry with her children, Michelle, Beau, and Peter, circa 1973.

Missing? How could he be missing? Casualties were a fact of life in the military. Men were killed in combat. But missing? It seemed incomprehensible.

The United States was in the middle of a war with North Vietnam, a country that was refusing to provide a full accounting of the American servicemembers it was holding captive as prisoners-of-war. Was Ed alive or dead? Was Sherry a wife or a widow? She would not know for four years.

The military had no structure or policy in place for families other than notification by a senior officer or a chaplain, who famously told one wife whose husband was a prisoner-of-war, “I’m here for you. I’m in my office Monday through Friday, 8:30 to 4:00.”

What’s worse, Sherry and other families whose husbands were missing or held captive were admonished to “keep quiet.” In the belief that the North Vietnamese would use any information as propaganda, Sherry and other wives in her predicament were told not to reveal to anyone outside of their immediate family that their husbands were captured or missing. As one MIA wife opined, “Now, how do you live like that?”

But they did. For a while.

This was, after all, the 1960s, and life was still very much like the 1950s. At the time, the median income was $6,600, the average price of a new car was just under $3,000, fuel cost 31 cents per gallon, and a first-class postage stamp was 5 cents. One dozen eggs cost 53 cents.

Homes had one rotary phone (and only one). Televisions often had rabbit ear antennae. Families played board games such as Mouse Trap, Monopoly and Trouble. Communication was more personal back then. There were only three television networks: ABC, CBS, and NBC. Most of America sat down to hear the news around dinnertime.

And what was life like for women in the 1960s? Many still wore white gloves when they went out to lunch. They rarely went out to dinner by themselves and they certainly did not travel by themselves. They worked as teachers, nurses, and stewardesses until they married and had children—as it was not uncommon for pregnant women to be fired from their jobs.

Women could not get a credit card, a car, or a mortgage without a man’s signature. No man, no mortgage.

Military wives of this era, like Sherry, had even more restrictions placed on them. They were expected to assist and support their husbands and their careers (or there were consequences for him); they wore their husbands’ rank, as many saw the women as extensions of their husbands; and they entertained a lot.

Each military service issued its own guidelines for wives. “The Navy Wife,” updated in 1955, was one such book. It painted a picture of an exciting and glamorous life for young women lucky enough to marry a naval officer: social activities, world travel, and exposure to national and international military leaders, diplomats, and politicians. The tome also issued a warning: Navy wives must get used to waiting. “What is more, they must learn to wait patiently…. In such situations it’s bad enough to feel tense and jittery, but it is worse to show it.” Wives had to love the Navy—and its hardships—as much as their husbands did. Military wives did not disparage the military; they did not violate the pecking order and protocols of the military; and they did not reveal their personal “burden” to anyone. Until Vietnam, this expectation permeated military culture.

President Lyndon B. Johnson (center) and Sherry (right in white hat).

It was against this backdrop that men like Lt. Cmdr. Martin shipped off to Vietnam, a small country that was unfamiliar to many Americans. The conventional wisdom was: how long would it take for a force as big and powerful as the United States military to defeat a country the size of New Mexico?

President Johnson’s advisers advocated for an air war. In March 1965, Operation Rolling Thunder kicked off and the sustained, aerial bombing of North Vietnam began. Pilots were shot down by the North Vietnamese. Hundreds of aviators and airmen went missing, and many were captured.

A black sedan, the harbinger of dreaded news, began showing up at the homes of aviators like Ed Martin. Like a raven circling around the neighborhood, the dreaded sedan came to deliver bad news. And it came for Sherry on July 9, 1967.

She was told that the U.S. government believed the prisoners were being well treated and authorities had every reason to believe that this condition would continue. After all, North Vietnam had signed the 1949 Geneva Conventions. Those countries who signed this treaty pledged to treat prisoners-of-war humanely: to give them adequate medical treatment, to feed them, house them, allow them to communicate with family, and to allow third-party inspectors at prison camps. Or so they thought.

Sherry (in checkered suit on the far right) with Bob Hope (center)

Families had powers-of-attorney lasting mere months, the length of time for a planned Vietnam deployment. Those quickly expired.

Government officials seemed plodding and often disinterested. They didn’t communicate with the women very often. They didn’t share information about other women and families in the same predicament. The women were isolated. Most suffered in silence.

The government was confident they could achieve a quick release of captive men through quiet, back-channel diplomacy. After all, that tactic had worked with other Cold War-era incidents, such as the shootdown of Gary Powers who flew a U-2 spy plane in 1962. His release two years later was considered a diplomatic triumph.

But days turned into months and then years of waiting. How would families manage financially, emotionally? They wondered: Were they wives or widows?

Fast forward to October 1968 when Sherry’s friend and neighbor Sybil Stockdale decided to break the silence. Married for more than two decades and the mother of four boys, Sybil was the wife of Navy Cmdr. Jim Stockdale. By October of 1968, he had been a captive of the North Vietnamese for three years. Sybil recognized that Hanoi was winning the battle of propaganda in the media. And she watched the antiwar activists claim that the American captives were being treated well.

She knew otherwise. With the help of intelligence officials, she and Jim had been exchanging encoded letters. She had become a spy. His secret messages revealed that the men were being tortured and placed in isolation for long periods of time.

Meeting with the State Department point man on the issue of missing and captive Americans, Ambassador Averell Harriman, she was unimpressed. He assured her that the United States government’s efforts on behalf of her husband were extensive but classified. In other words, she only received the proverbial pat on the head.

After three years of no progress, Sybil refused to keep quiet any longer. She bravely and boldly gave an interview to the San Diego Union. In it, she said:

“Where is the evidence, then, that Hanoi is a responsible government in the world community?” she asked. With defiance, she concluded, “The North Vietnamese have shown me the only thing they respond to is world opinion. The world does not know of their negligences [sic] and it should know!”

Syndicated around the country, many POW and MIA wives like Sherry read her interview. And it gave them the courage to go public, too.

Sherry and Sybil Stockdale, along with hundreds of other POW and MIA wives, rolled up their sleeves and, armed only with paper and pen, phone books and telephones, started writing and calling Washington. In January 1969, on the eve of President Richard Nixon’s inauguration, they deluged the White House with two thousand telegrams, urging the new president to “Please remember those who have offered so much for our country, the men who are prisoners of war in Vietnam. Don’t forget them now. Please insist on their immediate release through negotiations in Paris.”

They traveled to Paris for a showdown with the North Vietnamese, demanding an accounting of the missing men and better treatment for the POWs. They walked the halls of Congress and testified on the floor of the House and Senate. They traveled around the world, meeting with world leaders who could influence the North Vietnamese, like Pope Paul VI and Indira Gandhi. They appeared on national television and the covers of Life and Look magazines. They shook their fists at the Secretaries of Defense and State and urged President Nixon and Henry Kissinger to make the fate of the POWs a central point of negotiations at the Paris peace talks. Along with a Los Angeles-based student organization, they created the POW and MIA bracelets, metal cuffs inscribed with the name of one missing or captive man. More than five million of these bracelets were sold, effectively making the plight of our Vietnam POWs and MIAs personal for millions of Americans.

For Sherry, keeping busy with the other wives gave her purpose and staved off the loneliness and the dreams of reuniting with Ed—dreams she could not afford to have. “I generally forced myself to be so busy that by the time 9 o’clock came around, I was ready to go to bed. I’d fall into a deep sleep.” She had to stay focused on her reality: the war was not going to end any time soon, which meant her husband faced years in captivity.

Above: Sherry Martin and Sybil Stockdale with the San Diego Union reporter.

Below: Ed Martin’s POW Bracelet

As Doug Mustin St. Denis ’55, a neighbor and friend of Sherry’s, remembered, “Sherry began every sentence with ‘When Ed comes home.’” She never lost her faith. In a letter Doug wrote to Ed when he came home, she wrote about Sherry: “[She is] a beautiful, courageous lady, and if she ever for one moment gave up hope, she certainly kept it a secret.”

By 1972, a Harris poll concluded that 75% of Americans believed the United States should stay the course in Vietnam until all the POWs were released. The fate of the 591 men had become central to peace negotiations, eclipsing the fate of the thousands who were fighting and dying on the frontlines. That’s how influential these women had become.

Every war produces prisoners. But only since the Vietnam War have prisoners become political hostages, so valuable that preventing them in future wars has become a strategic imperative—not for humanitarian reasons, but to avoid having to make compromises to get them home.

Today, the United States will still tolerate casualties, but we will not tolerate missing men or POWs. We now expend unlimited resources, deploying special forces to rescue just one POW, whether that man is in Bosnia, Iraq, Somalia, or Afghanistan. This fundamental shift in American policy was initiated by this small band of wives.

And when the Paris Peace Accords were finally signed in January of 1973, and Ed Martin and the other 590 men were released—some after more than eight years in captivity—their homecoming was a national celebration. Americans got up in the middle of the night to watch their release live on national television. While most Vietnam veterans returned home to an ungrateful nation, the Vietnam POWs received homecoming parades, keys to the city, lifetime passes to Major League Baseball, free vacations, national media tours, and a celebrity-studded White House dinner.

And what about the missing men? More than 2,500 remained at the end of the war. The organization that these wives created, the National League of Families, continued to lead the charge to account for them. They forced the U.S. government to form a permanent agency dedicated to a full accounting of the missing. That agency, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, still combs the globe in search of remains of missing service members from all wars.

Often, newspapers cover stories about a family’s husband, father, grandfather, uncle, brother, or son whose remains are repatriated six or seven or eight decades after their loss. Families are stunned to learn their loved one has never been forgotten. Prior to the Vietnam War, this did not routinely happen. Until the Vietnam War, we left our missing—missing.

The iconic black and white POW/MIA flag created by these women, the one that flies above the White House, the Capitol, and every post office in the United States is a reminder of our national commitment to “leave no man behind.”

We have a handful of gutsy women, like Sherry Martin, to thank for that. They were resolute in their commitment, refusing to keep quiet. They were… unwavering.

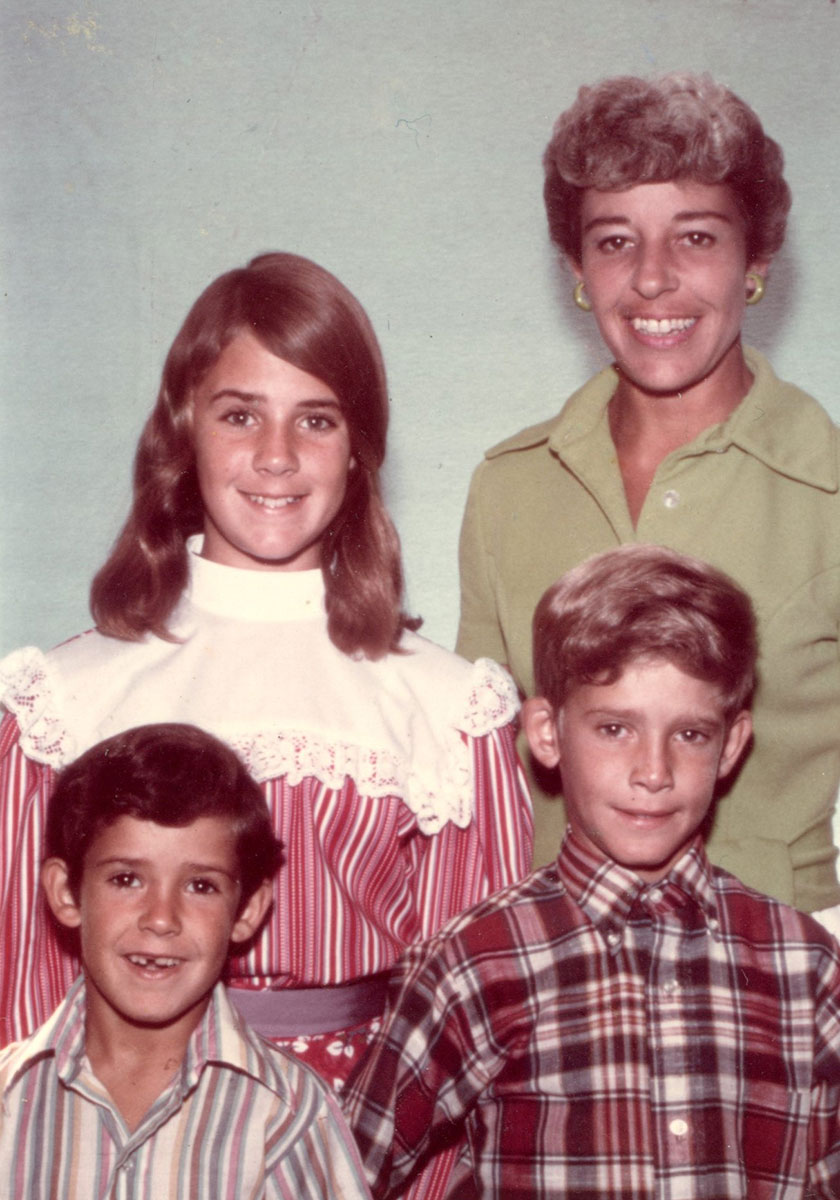

Above: Sherry’s St. Agnes senior portrait

Below: 1952 St. Agnes Green Team Basketball Squad

About the Author and Photographer

Taylor Baldwin Kiland ’85 (mother of Kiland Hatcher ’31) is the coauthor of “Unwavering: The Wives Who Fought to Ensure No Man is Left Behind,” from which this article is adapted. Also featured in the book is Sidney McCain, St. Agnes Class of 1985, and Hunter Ellis, St. Stephen’s Class of 1986. Portrait photographer in this article is Jamie Howren ’85. Like Sherry Martin, Taylor, Jamie, and Sidney were also members of the Green Team.

MORE ABOUT SHERRY

The daughter of a naval officer, Sherry Handly Martin grew up moving every 2-3 years. An only child, she transferred from the Brooklyn Friends School to St. Agnes in her junior year, when her father took an assignment in Washington. At St. Agnes, she played field hockey, basketball, and tennis, and was a member of the Green Team. She would have preferred to wear a uniform, because “It’s easier to know what you’re going to wear.” But she did not like the P.E. uniforms, “Who would like green bloomers, for heaven’s sake?”

Sherry’s family has deep generational ties to Coronado, where they have maintained homes since the early 1900s. She migrated back there after college, where she met Ed at a party of naval aviators. Seeing Ed from across the room, she said, “He came in and just sort of plopped down. I sorta plopped down on top of him.” Was it love at first sight? “No. I don’t think I knew anybody that had love at first sight. Or nobody that would admit to it, anyway.” They married in 1958 and had three children.

While he was in captivity, Sherry kept a collection of scrapbooks where she assembled photos, her children’s artwork, letters, party invitations, telegrams, and diary entries she wrote to herself and to Ed. She even sent herself wedding anniversary cards. You can see some of the personal collection here on the SSSAS magazine website, sssasmagazine.org.

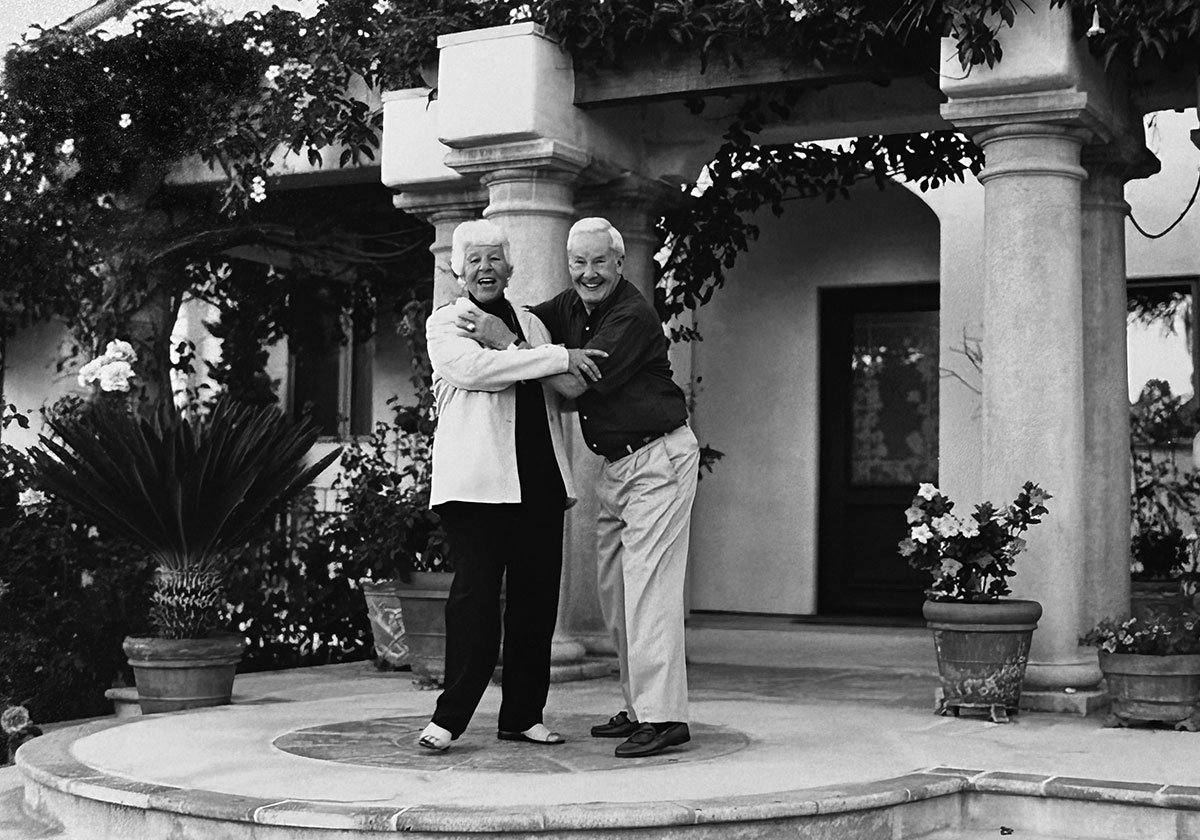

Sherry and Ed had a happy ending: Ed was released on March 4, 1973—after more than five years in captivity. He continued his naval career, rising to the rank of vice admiral. They enjoyed another 40 years of marriage until Ed’s death in 2014.

SHERRY MARTIN’S SCRAPBOOK

POW wife Sherry Martin kept a series of scrapbooks, where she collected and documented her family’s life while her husband, Navy Lt. Cdr. Ed Martin was in captivity in Hanoi. Photos, party invitations, newspaper clippings, her children’s artwork, and messages to their mom and dad–as well as letters and cards she wrote to Ed (but could not deliver), were carefully preserved in these albums. They are a vivid history of her life during the Vietnam War. All photos courtesy of the Martin family.

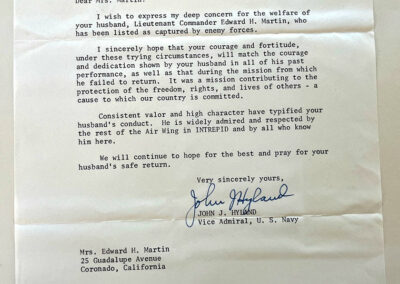

July 18, 1967 Letter from the Navy

Shortly after Ed’s plane was shot down in July of 1967 and he was listed as missing in action, Sherry received this condolence note. Expressing “concern” was about all the authorities were doing at this point in the war, despite the hundreds of men held captive and missing.

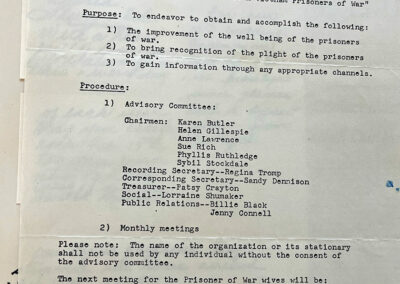

February 20, 1968 Creation of the League

After more than three years of keeping quiet, the wives decided to get active. They quietly created an organization. They learned quickly that they had power if they showed the strength of their numbers.

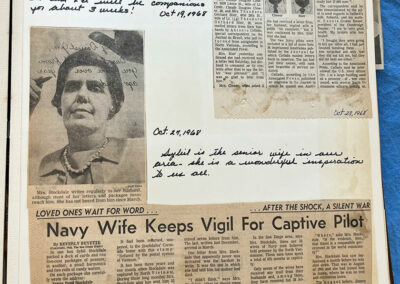

October 27, 1968 article in the San Diego Union

Coronado POW wife Sybil Stockdale broke the silence imposed on the wives of the POWs and MIAs when she gave an interview to the San Diego Union in October 1968. By that time, her husband had been captive for more than three years. As Sherry’s handwritten note says in the margin, Sybil inspired many of the other wives to speak out, too.

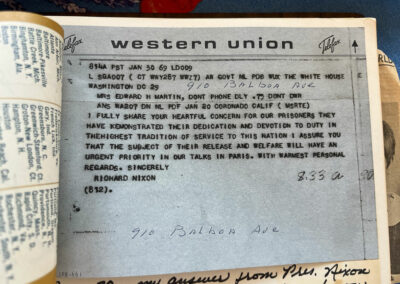

January 30, 1969 Telegram from President Nixon

On the eve of Richard Nixon’s inauguration, families of the POWs and MIAs deluged the White House with telegrams, demanding that the newly elected president make the fate of their husbands a national priority (something President Johnson did not do). More than 3,000 telegrams, including one from Sherry Martin, landed on his desk and he replied to each one.

November 28, 1969 Palm Springs Visit

Shelly and Beau Martin appeared with Santa Claus in front of the cameras over the holidays of 1969, at an event hosted by the Palm Springs Navy League for families of the missing men. The children of our POWs and MIAs were frequently used in the media to generate sympathy among Americans

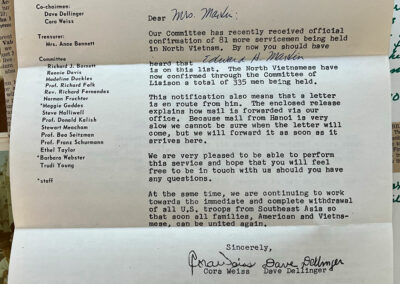

April 7, 1970 COLIAFAM Letter

The Committee of Liaison was a group of antiwar activists who worked with Hanoi to ensure it was the sole intermediary between the POW families and the North Vietnamese government–excluding U.S. officials. All mail and communications was processed and transported through COLIAFAM. It was humiliating for the U.S. government, but that was the objective.

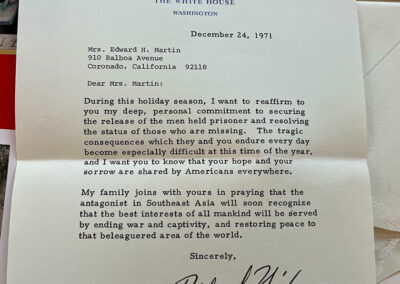

December 24, 1971 Christmas Letter from President Nixon

A personal holiday letter from the president might be a small consolation, but at least the wives knew they had Nixon’s ear. Note that he places the responsibility for ending the war squarely on the plate of the “antagonist.”

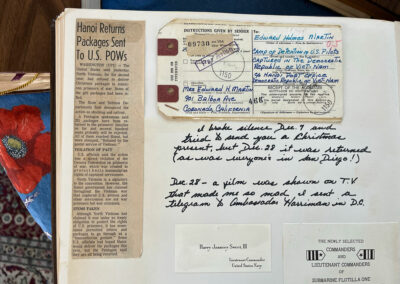

December 28, 1971 Notice that Christmas packages were returned

The women got bolder and more assertive as the war waged on with seemingly no end. Sherry’s attempts to get a Red Cross package to her husband in captivity were unsuccessful. Hanoi continued to defy the Geneva Conventions, requiring the regular flow of mail to and from prisoners. So, she went straight to the top at the State Department to lodge her formal complaints.

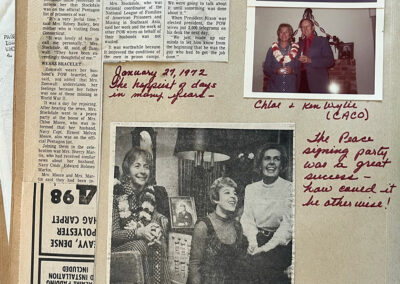

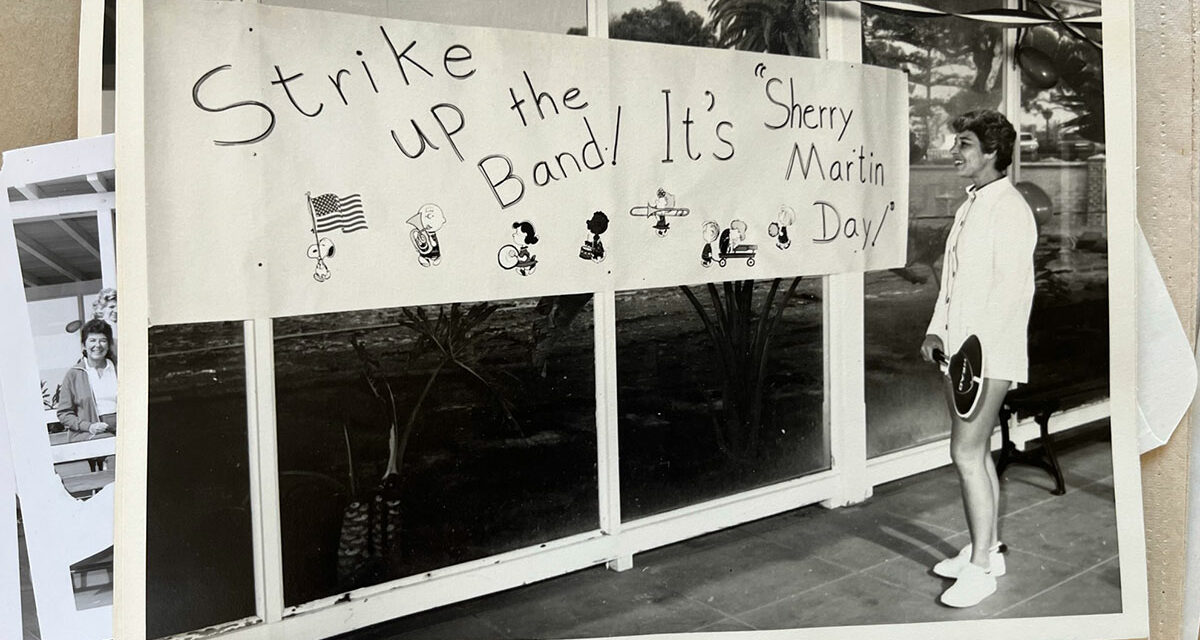

January 27, 1972 “Wives Rejoice” article

Coronado POW wives Chloe Moore, Sherry Martin and Sybil Stockdale held a “peace signing party” upon hearing the news that the Paris Peace Accords were finally signed on January 27, 1973. The Accords stipulated that all prisoners of war held in Hanoi would be released within 60 days.

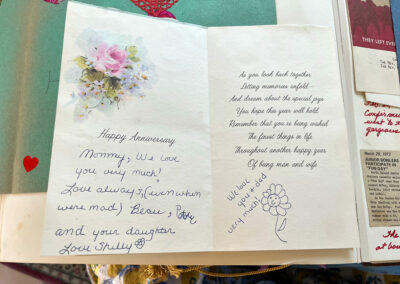

1972 Anniversary card from the Martin children

Sherry and Ed’s children Michelle (“Shelly”), Peter and Beau obviously knew how hard wedding anniversaries were for Sherry during the war.

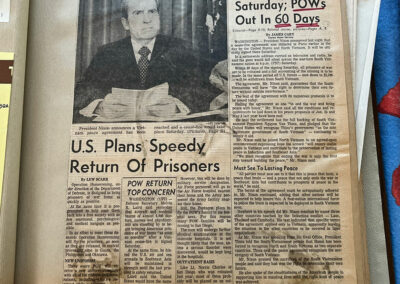

January 24, 1973 “Cease Fire Pact” article

After more than eight years in captivity, this front-page article announced the news the POWs and MIAs had been waiting for: the Paris peace talks had finally resulted in an agreement and the men would finally be released.

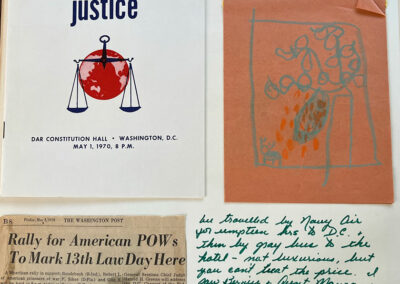

May 1970 Appeal for International Justice Rally

Sen. Robert Dole and businessman Ross Perot pledged to help the POW and MIA wives get attention from Capitol Hill by filling the seats of DAR Constitution Hall on May 1, 1970. Family members of prisoners of war and those missing in action were determined to enlist the support of Congress to put international pressure on Hanoi. This is the program and other mementos from the event and Sherry’s trip to DC to participate in this “Appeal for International Justice,” attended by more than 3,000 family members, senators and congressmen, State Department and Pentagon officials. The event made national news.

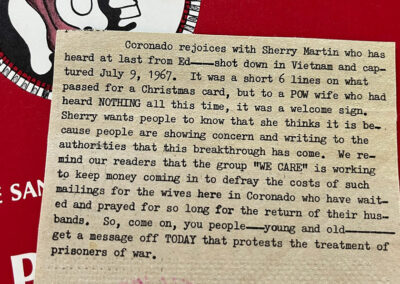

The community of Coronado rejoiced that Sherry heard from Ed

Almost three years after Ed’s disappearance over the skies of North Vietnam, Sherry receives official word that he is, indeed, alive and in captivity. But it would be another three years before he returned home.