The Flâneuse

The Flâneuse

In Conversation with Artist Constance Mallinson ’66

BY ANDREA DAWSON

For a painter, sculptor, and critic at the helm of the Los Angeles artmaking scene for more than 40 years, Constance Mallinson ’66 is disarmingly tender. She laughs easily. She explains the sociopolitical nuances of Postmodernism to a naive reporter with nary a hint of annoyance. It should come as no surprise that she has been a skilled teacher of her craft for nearly as long as she has been a successful practitioner.

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

Selection of Solo Exhibitions

• Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles)

• Museum of Art & History (Lancaster, Calif.)

• Jason Vass Gallery (Los Angeles)

• Armory Center for the Arts (Pasadena)

• Pomona College Museum of Art

• Culver Art Center (University of California, Riverside)

• The Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery

• Angles Gallery (Los Angeles)

• National Academy of Sciences (Washington, D.C.)

Public Collections/Art

• Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles)

• San José Museum of Art

• Los Angeles County Museum of Art

• EXPO Line MTA Bergamot Station permanent artwork installation (Los Angeles, in conjunction with her eldest daughter, a digital artist and animator)

• MTA Red Line poster series (Los Angeles)

• Newport Harbor Art Museum

• “Coolglobe” artist

• Wilshire Grand Hotel mural (Los Angeles)

Awards

• National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship recipient

• City of Los Angeles Artist’s Grant recipient

• Santa Fe Art Institute Residency Award

• Djerassi Foundation Residency Award

• California Supreme Court mural finalist (San Francisco)

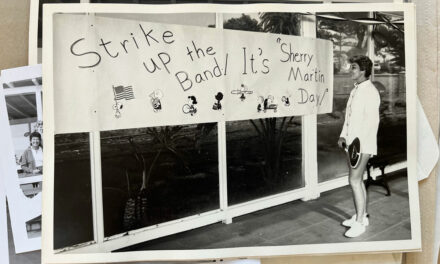

By her own admission, however, her gentle manner belies a contrarian streak. Fake ID in hand, she began sneaking into the beatnik coffee houses of Washington, D.C. in the early 1960s, one of the few venues at the time daring to showcase contemporary art, a stone’s throw from the National Gallery of Art. Ever since, she has channeled a certain edge, an intense desire to remain engaged, relevant and curious; to make her viewers think. As one Los Angeles Times critic wrote, her interest is “in exploring art that [lies] outside the dominant canon.” She often counsels her students: It’s ok to be a little angry.

Los Angeles in the 1970s and ’80s was fertile ground for artists, and Constance—who relocated to California with her filmmaker husband in 1979—flourished. Before long, she became an integral contributor to the largely female-driven Pattern & Decoration Movement, which sought to question the rigid norms of Minimalism by injecting feminist flair. At a 2020 Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition, the first of its kind—“With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art, 1972–1985”—she was among the artists featured. Acknowledging the nature of the exhibition as a historical survey, she laughed, “I never anticipated being historical!”

Constance’s involvement in the movement is but one chapter in a fearless and ever-evolving artistic career. Over the last four decades, her repertoire of work and accolades in Los Angeles—not to mention prolific teaching at numerous colleges and universities in southern California—are testament to her enduring mark on the West Coach art world. From the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art to the San José Museum of Art, her paintings can be seen in major private and public art collections across California.

Here, Constance, 73, a mixed-media representational artist and a committed flâneuse (her word), shares early career memories at St. Agnes and in D.C.; the challenges she has faced as a female artist and mother; her deep concern for the environment; and what keeps her pursuing her craft, nearly 50 years after her first gallery exhibit.

Your St. Agnes senior yearbook entry indicates how admired you were among classmates and faculty alike for your artwork. As art editor of the 1966 “Lamb’s Tail,” you designed and drew the cover and dividers. Clearly, art was important to you at an early age. What led you to pursue art as a career?

CM: It was a combination of factors. My parents were very encouraging and, later, my schoolmates. I had art lessons from a very early age with a local art star in Alexandria. There was an older woman, Ms. Downs, at St. Agnes who taught art, but it was extracurricular. Art was pretty marginalized in those days at school; it took a back seat to music. I remember staying up late working on my oil paintings on the kitchen counter just because I wanted to. It was really important to me. I sold my first painting at St. Agnes, to an administrator, I think—it was a pastoral scene with some big trees and sheep. I’ll never forget how excited I was. So, you combine my passion with the encouragement and serious instruction I received, and it all adds up to a drive. I was pretty confirmed by the middle of high school that this is what I really wanted to do. Washington, D.C. is also a great museum town. I would often take the bus for an hour to get to the Mall and spend the whole afternoon at the National Gallery, looking at the Rembrandts and Monets. And I’d sneak into the beatnik coffee houses, where they hung edgy art and played bongos and jazz. For a 14-year-old that was an amazing eye-opener. I realized then that there was this very cool contemporary art scene going on. That was a big part of my early education as well.

You received a BFA from the University of Georgia in 1970. What led you to Los Angeles?

CM: I had planned to pursue a master’s degree after college, but I got married and my husband, Eric, and I started a business. He was a filmmaker and we made documentary and informational films for the government. It was really fun. I have a picture of Eric with Jimmy Carter for a film we did for the Department of Energy. I also had my first serious studio right after college, which I continued to maintain while we worked. And I was exhibiting. Then I got a lucky break. I entered a competition and the head curator of the National Gallery was the judge. The award, which I received, was an exhibition at the Alexandria Athenaeum. He also recommended me to a renowned gallerist who owned a contemporary gallery in D.C., Henri Gallery. I started showing with her pretty regularly. We had our film business for 12 years, but my husband got antsy to be in Hollywood. In 1979 we moved out to California. I was out of the film thing at that point, but I continued to do my art. It proved to be a very good move for me— Los Angeles had a much more lively, exciting contemporary art climate. I met a lot of artists, a lot of galleries were opening up. It was booming. I didn’t look back.

It was a provocative time in Los Angeles, not to mention across the United States—the Women’s Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Feminist Art Movement, Minimalism, the Pattern & Decoration Movement. In what ways did these movements factor into your early career?

CM: They factored into my career quite a bit. Contemporary art is really about channeling the zeitgeist through your personal lens into the artwork. I was very involved with Feminism, which had a big presence in Los Angeles. The Pattern & Decoration Movement was based in a lot of feminist theory, arguing that Minimalism was entrenched at the time and pretty male-dominated; it was against any personal narrative. Art had to be cold and clinical. Then the feminists came along and said hey, we want to get personal here and tell our stories. Pattern & Decoration artists introduced color and pattern, and influences from women’s crafts, like weaving and textiles. Things that were considered lowly pursuits in the world of high art were radically introduced. In the early 1970s it was very difficult for female artists and artists of color to get museum shows. It was necessary to kill that system of “this is the movement and if you don’t fit into it, we’re not interested.” The idea that any one movement could prevail at any given time came to an end then. Pattern & Decoration was one of the last major art movements of the 20th century.

“What’s most important to me as an artist is to stay engaged and excited about what I’m doing— to feel that there’s still room to explore, that painting is not mired in tradition. There’s still a lot to say.”

Critics have praised your work for its willingness to push against and question artistic conventions. Do you agree? And what are you most interested in exploring through your work?

CM: You have to consider that contemporary art, or the tradition of Modernism, relied on positioning itself outside of the prevailing taste. That notion of progress—of moving culture forward—has always attracted me. I’ve always wanted to have my finger on the pulse of the moment. I’m a bit of a contrarian. It fit. Hopefully I still have a bit of that in me. There are consistent threads you can point to in my work. It has constantly played on the line between abstraction and figuration. Most if not all of my work has figurative elements to it, but it also includes that “all-overness” of abstraction. The environmental crisis weighs so heavily on me, so I want to address those themes in my work. Sure, you can just make something nice for a wall, but that’s not enough for me. I like challenging content. What am I saying with this painting? How do I harness my formal strengths—the color, my technical skill and rendering, my composition—and say something at the same time? That’s the dance.

“The support that you get and also give to your fellow artists is really important. That’s something that took me a long time to find out.”

The tension between the natural environment and global consumerist forces are an obvious through line in your work. You are well known for transforming cast-off plastic and other detritus found on your daily walks around Los Angeles into arresting, large-scale landscapes. How much of artmaking is for you, personally— a way to process your feelings and worries—and how much is intended as a statement for others to respond to?

CM: As an artist, it’s your job to make people look at a painting. And once they’re looking at it, your job is to make them think. Ultimately, gauging the efficacy of what I’m doing is very hard, unless you have an opportunity to talk to viewers. Art viewers are pretty smart; they wouldn’t be [in a gallery or museum] if they didn’t want that kind of experience or enrichment. Artists aren’t going to stop Exxon from drilling for oil. We’re not going to stop corporations from cutting down the Amazon. But we are a link in the chain, the cultural chain that consists of artists, musicians, writers, journalists, politicians, volunteers. We’re contributing to the dialogue. It’s easier for me to process [environmental concerns] when I think of myself as part of something rather than as a sole actor. Artists are in a fairly unique position to bear witness to what’s going on.

In an interview a few years ago you addressed the challenge of being a female artist—and a mother—and navigating the perceptions surrounding those two identities. What was that like?

CM: Very challenging. I was raising two daughters and balancing my professional life, and I was teaching, too. I just powered through it. I don’t know how I did it, frankly. Then there is the undeniable dissing of mothers. And a desire to be taken just as seriously when you’re driving your kids to soccer practice as before you had children. There was a long stretch when I was not finding a lot of opportunities to exhibit. I had my studio at home, so I was fortunate. While they were at school I would work for six hours. What fell off for me was the socializing and the connection-making. You can’t keep going to art parties when you’re raising kids. Once they’re through college and they leave the house, your time is your own. It’s important to communicate to young women and students that [motherhood and a professional life] are not mutually exclusive but mutually supportive. But you’ve got to be really organized and determined.

I’m sure you had a notion when you graduated from college—or perhaps earlier—of what life as an artist might look like. What part of that vision has come true, and what has ultimately been different from what you anticipated?

CM: When you’re 21 it’s like, bring on the world! I never really questioned myself significantly in terms of my drive and my desire to be in the studio. That was always number one. I knew I had to focus and create the work in order to have a career. I also knew I wanted to have a good time. Artists are a lot of fun—there’s lots of partying and a lot of camaraderie. I made it a point to meet other artists and still do to this day. I love the social life that goes along with knowing these incredible people. As far as expectations of fame and glory, we lived through the Warhol fascination and The Factory. That was the popular sense at the time of what an artist’s life was about. That wasn’t why I felt I was in it; I’ve never been a celebrity person. It doesn’t interest me. But at the same time, if that’s the prevailing age, you have to struggle with how you see yourself versus what the culture expects. Do you want to be a TikTok star or do something else? That is today’s analogy. It takes a little courage to follow your own instincts and do what you think is important, what is more you. The community part I was also not prepared for as a younger artist, where it’s all about “me.” Then you find, of course, that community is really important. Today, the art world is much bigger than I ever thought it would be, and there is so much more competition. More MFAs are graduating. Not only are you trying to maintain the momentum of your own practice, you have these upstarts who are trying to knock you off the mountain! The main things I have always been so gratified by are how much I personally love making art, the fabulous community of artists I belong to, and the never-ending excitement for the work that comes out.

“There have been times when I’ve wiped off an entire day’s work of painting. But you have to be able to do that. You can’t be too precious about your work.”

What are you working on now that excites you?

CM: I just finished a piece that’s going to a big show next week [“Mapping the Sublime: Reframing Landscape in the 21st Century,” at the Brand Library & Art Center, through June 11]. It’s a hybridization of painting and sculpture, which is really intriguing to me at the moment. I’ve never worked in three dimensions before. I gathered blocks of styrofoam that I found on my walks and I painted on them all these endangered landscapes and animals. I got so sad making this thing I just had to quit at times! These little animals would be looking at me… It was very emotional. Hopefully the viewers who engage with the piece will be moved, too. That’s all I can do, really, is to move people to bear witness to our consumptive greed and habits. Also, as I get older, and now that I have had two children of my own, I want my artwork to engage younger people. This styrofoam piece will be mounted at kid-height on a pedestal. I’m still doing two-dimensional paintings as well. There’s a lot of freedom to experiment in the air, which appeals to me rather than sticking to tradition so strictly. One of the nice things about being at this stage in my career is that I just want to do what I want to do. I don’t need to please anyone but myself right now.

When you look back on your career today, and remember yourself on the cusp of graduating from St. Agnes, what are some bits of wisdom you wish you had known then?

CM: Well, there are all the clichés… cultivate your passion, water that garden, make sure it grows and is fertilized. There is no career without that. Have patience, gratitude, a good sense of humor, a willingness to erase and start over. Be curious. Be furious. Be mad when it serves you well. And remember, artmaking is meant to be enjoyed. If you’re not enjoying it, you shouldn’t be doing it. You will get discouraged. You will think you’re the worst artist in the world. That’s natural. Sometimes the plants that you’re watering every day will just die. But if you keep planting and nurturing, they will flourish. If you stick with it, it is a tremendously gratifying life to be an artist.