A Teacher of Faith

A Teacher of Faith

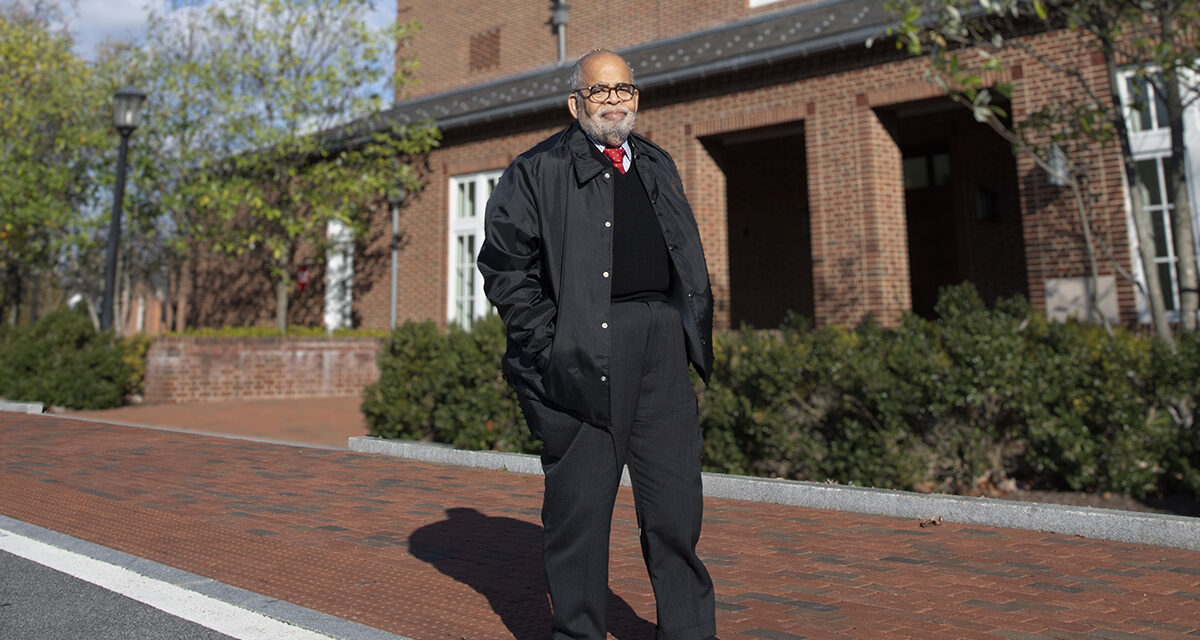

Reverend Lloyd Alexander “Tony” Lewis ’65

BY ANDREA DAWSON

It was early September, 1961, when the Reverend Lloyd Alexander “Tony” Lewis, Jr. ’65 arrived at St. Stephen’s Upper School entrance, wearing a coat and tie and a hint of freshman apprehension. His matriculation was auspicious. It not only marked the beginning of a high school journey that would launch him into a life of ministry and distinguished scholarship; as the first Black student to attend the school, his arrival also marked the beginning of integration at St. Stephen’s, the very first church school in the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia—indeed, among the first private schools in all of Northern Virginia—to put an end to segregation.

More than 60 years later, his framed St. Stephen’s diploma is proudly displayed on his bedroom wall. A local newspaper article, taped to the back, serves as a reminder of his first day. “St. Stephen’s School of Alexandria admitted its first Negro student this fall as quietly as possible,” reads the first line. At the time, the phrasing struck him as curious. Just a few blocks away, Hammond High School was also in the midst of desegregation, but it was not quiet. It wasn’t until several years later that he would learn, from a few high school friends, the full implication of the wording—and why his arrival, indeed his entire St. Stephen’s experience, in a southern city mired in the politics of the time, was so oddly uneventful.

One gets the sense that quiet, impactful achievement and purpose have driven the way Tony Lewis, now 75, has lived much of his life. After St. Stephen’s, he would go on, with little fanfare, to become the first African American from Alexandria to be ordained into the Episcopal ministry, and one of the first to hold a faculty position at the Virginia Theological Seminary, where he was also a student.

“Somebody has to break the ice. Where I was at various points in my life I got to do some ice-breaking. It wasn’t something of which I was particularly conscious. It wasn’t something my parents and I discussed at the dinner table,” he recalls. Bookish and focused from a young age, his central concern when he arrived at St. Stephen’s: getting a good education. And figuring out what, if anything, was meant by this nudging feeling he had about wanting to pursue a life calling that originated in his faith.

An only child growing up in Alexandria, Tony’s father was a funeral director and his mother served as the administrative assistant to the principal at the Black public high school, Parker-Gray. Church figured centrally in his childhood. So did the sense of community and service that arose from it. “I can not think of a time when church was not part of what I did and who I was. For a lot of us who are African Americans, the church really provided a context for being able to live,” he says.

He remembers Mr. Hammond, a house painter and his Sunday School teacher, piling a classful of rambunctious boys into his station wagon on Sunday mornings to deliver orange sherbert to elderly parishioners. “What he modeled was that the church does not see itself as something that’s confined to four walls but something that has a far wider influence—not only on one’s own life but also on people in the community.” That expansive notion of the church and the potential of its influence stuck with Tony. It was on his mind when he got to St. Stephens, following a primary education at the nearby, already-integrated Burgundy Farms Country Day School.

Head of School Kirsten Adams, Tiffeny Sanchez, Tony, and Maggie Hoy Heckman ’75

Unsure of his path—his parents steered him towards becoming a doctor—but drawn ever closer to the idea of becoming an Episcopal priest, he walked into the office of Headmaster The Rev. Emmett H. Hoy (1955-1975) one day. “I have this feeling about something, and I wonder if you could help clarify it for me,” he remembers asking him. Dr. Hoy was pleased, but practical. His response, as Tony recalls: “Go off and be an undergraduate. Drink as deeply of that water as you possibly can. If after four years this gnawing thing is still there, we’ll talk again.”

Tony returned to Trinity College, Hartford on May 22, 2022, to receive a Doctor of Divinity, honoris causa conferred upon him by the college.

So, Tony headed to New England, where he took in all that was offered by its vastly different culture and the academic challenges of Trinity College. After four years, as one of only three Classics majors in his graduating class, the “feeling” remained. His junior year, he attended the Bishop’s Advisory Conference for Applicants for the Ministry (BACAM) in Richmond, an annual conference that helps those considering priesthood decide if the vocation is right for them. By coincidence—perhaps providence—the academic advisor assigned to him was Dr. Hoy. A deeply personal, introspective exercise, the work of the conference was not to be undertaken with an acquaintance, much less one Tony so greatly admired. Neither seemed to care. “Shall we tell them?” he remembers Dr. Hoy asking him, a twinkle in his eye. “No!” his student replied.

Not long thereafter, Tony’s course was set. He returned to Alexandria and the Virginia Theological Seminary (VTS), just blocks from St. Stephen’s, to earn his Master’s degree in Divinity. Two days after graduation, he was ordained a deacon; six months later, on Dec. 2, 1972, he was ordained a priest, only the second alumnus from St. Stephen’s at the time to be ordained.

His passion for scholarship and teaching remained strong. So did his interest in developing students for pastoral ministry. Unlike teaching at a college or university, being an academic in a seminary would allow him to pursue both. But first, he knew he needed on-the-ground training.

After ordination, he relocated again, this time to Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where he served for two years as a full-time parish minister at St. George’s Episcopal Church. After years of classroom study and research, it was a formative experience, one that crystallized his decision to pursue teaching in a seminary setting. “If I was going to help form people for parish ministry, it made sense for me to have the experience of being a parish minister,” he reflects. “You want to know what people are going to face before you teach them.” Even now, in a state of semi-retirement, parish connections are essential to Tony.

In the fall of 1974, he returned to Connecticut to further his studies. Harvard as well as Union Seminary in New York City accepted him into their graduate programs, but he chose Yale for the reputation of its doctoral program in Biblical Studies.

At the end of four years—and three summers spent holed up in steamy Yale classrooms learning French and German, in addition to the Latin, Greek, and biblical Hebrew he already knew so that he could decipher ancient texts—VTS came calling. They were intrigued by the direction of his scholarship and keen on wooing him back to their campus to teach (he completed his dissertation in New Testament Studies in 1985).

Ten years after retiring from VTS, Tony has hardly shed his mantles as educator and priest. Nor does he have plans to. Every Thursday and Sunday he participates in services at St. Paul’s Church in Foggy Bottom. He lectures and teaches adult education classes in parishes up and down the East Coast, including, recently, the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, in Times Square. And then there’s Zoom, which has provided him with a delightfully unexpected medium for reaching a broader audience. “I can sit in my bedroom wearing a clerical shirt and sweatpants and teach in Rochester, New York and California, all in the same day,” he jokes.

Teaching, preaching, listening, and learning—the ongoing search for meaning and understanding in a community of equals—continue to propel Tony’s life and work. In their own way, they were messages that were quietly but boldly modeled by Headmaster Hoy and others who taught him from the very first day he arrived at St. Stephen’s that September morning in 1961.

Unknown to Tony at the time of his landmark enrollment was the underlying tension that surrounded it. While he more than qualified academically, St. Stephen’s School Board disagreed on whether or not to admit a Black student. So committed was Headmaster Hoy to the integration of the school that, when the Diocesan trustees met to discuss Tony’s application and ultimately overrule the Board, he had tucked in his pocket a letter of resignation, ready to furnish if the decision had gone the other way.

Similarly discreet, behind-the-scenes gestures involving students, parents, and faculty alike—notifying them of the school’s imminent integration—paved a path for Tony. (In his 2009 graduate school thesis on the integration of southern Episcopal schools, Wade H. Morris, Jr., a former history teacher at St. Stephen’s, recounts Headmaster Hoy calmly explaining to a parent and prominent anti-integrationist that he was welcome to withdraw if he disagreed with the school’s position.) Though he never once spoke of these actions, their impact on Tony’s experience at St. Stephen’s, not to mention the trajectory of the school in the decades to come, was seminal.

“Emmett Hoy really exhibited in my mind the best of what it meant to be part of the Episcopal Church in Virginia,” Tony says. “He was committed to what his faith taught him about being a human being and a child of God. He was so much a part of the school’s change of direction and heart at that time, my role was incidental in many ways. I just got up that September and went to a new school.”

Up until Dr. Hoy’s death in April of 1975, Tony—his former student-turned-close-colleague—felt privileged to pay him regular visits. Integrity, purpose, and gratitude were themes that arose in their conversations until the very end. They are themes Tony continues to lean on, lean into, and teach. “To me, the most important message is that there is a good deal that one can be happy about. So many things today seem to be causes of angst. There is happiness to be had in the joy of learning just like there’s happiness in the joy of believing.”

Through the generous Campaign support of the Brown-Sanchez Family, the Upper Commons of the reimagined Upper School, will be named in honor of Rev. Tony Lewis ‘65 and former headmaster Rev. Emmet Hoy.

Footnotes

Like all St. Stephen’s boys at the time who took English with Willis Wills, Tony was made to memorize the prologue to Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, a secret handshake, of sorts, for identifying others who attended the school. He can still recite it by heart.

Fascinated by languages, Tony teaches Greek, Latin, and Biblical Hebrew; reads French and German; and dabbles in Spanish and Dutch.

From an early age, Tony was—and remains—an avid pianist. In high school, he earned entry into a program run by Howard University’s Department of Fine Arts where, twice a week after St. Stephen’s classes, he studied with their piano faculty. His graduation from St. Stephen’s coincided with his completion of the program, earning him a certificate in musical theory and piano performance.

Thanks to his mother’s position at the nearby public high school, Parker-Gray, Tony was “something of an amphibian,” he explains. “As I went through grade school and then high school, I had my foot not only in whatever independent school I went to but also in the public school system in Alexandria. It meant that I was always doing both in terms of the racial environment in which I was living and learning.”